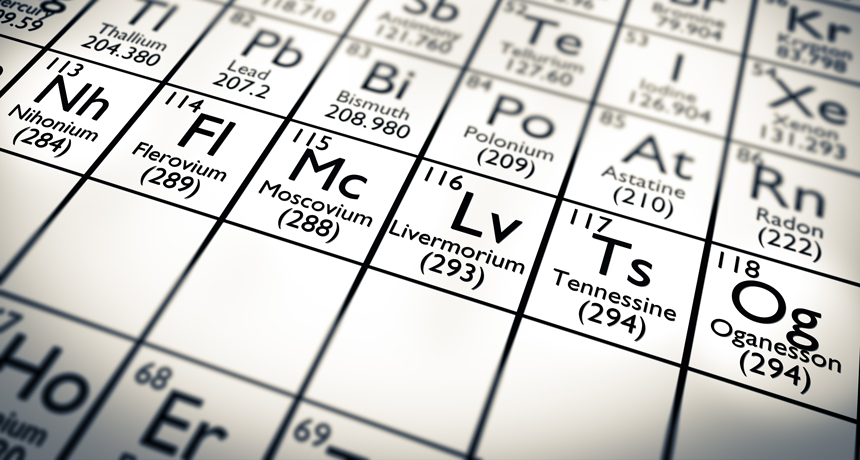

5 ways the heaviest element on the periodic table is really bizarre

The first 117 elements on the periodic table were relatively normal. Then along came element 118.

Oganesson, named for Russian physicist Yuri Oganessian (SN: 1/21/17, p. 16), is the heaviest element currently on the periodic table, weighing in with a huge atomic mass of about 300. Only a few atoms of the synthetic element have ever been created, each of which survived for less than a millisecond. So to investigate oganesson’s properties, scientists have to rely largely on theoretical predictions.

Recent papers by physicists, including one published in the Feb. 2 Physical Review Letters, detail some of the strange predicted properties of the weighty element.

- Relatively weird

According to calculations using classical physics, oganesson’s electrons should be arranged in shells around the nucleus, similar to those of xenon and radon, two other heavy noble gases. But calculations factoring in Einstein’s special theory of relativity, which take into account the high speeds of electrons in superheavy elements, show how strange the element may be. Instead of residing in discrete shells — as in just about every other element — oganesson’s electrons appear to be a nebulous blob. - Getting a reaction

On the periodic table, oganesson is grouped with the noble gases, which tend not to react with other elements. But because of how its electrons are configured, oganesson is the only noble gas that’s happy to both give away its electrons and receive electrons. As a result, the element could be chemically reactive. - Solid as a rock?

Oganesson’s electron configuration could also let atoms of the element stick together, instead of just bouncing off one another as gas atoms typically do. At room temperature, scientists expect that these oganesson atoms could clump together in a solid, unlike any other noble gases. - Bubbling up

Protons inside an atom’s nucleus repel one another due to their like charges, but typically remain bound together by the strong nuclear force. But the sheer number of oganesson’s protons — 118 — may help the particles overcome this force, creating a bubble with few protons at the nucleus’s center, researchers say. Experimental evidence for a “bubble nucleus” has been found for an unstable form of silicon (SN: 11/26/16, p. 11). - Neutral territory

Unlike oganesson’s protons, which are predicted to be in distinct shells in the nucleus, the element’s neutrons are expected to mingle. This is at odds with some other heavy elements, in which the neutron rings are well-defined.

For Oganessian, these theoretical predictions about the element have come as a surprise. “Now it’s up to experiment,” he says. Predictions about the bizarre element could be put to the test once a facility for creating superheavy elements, under construction at Oganessian’s lab in Dubna, Russia, is up and running later this year.